|

| Demosthenes |

Demosthenes was the most famous orator of ancient Athens and a principal voice in the attempt to maintain democracy in the face of the threat of the tyrannical Philip of Macedon and his son Alexander the Great. He is remembered largely because of the many speeches he left behind. Many details of the life and times of Demosthenes are recorded in Plutarch’s biography.

Demosthenes was the son of a sword maker of some substance, but after his father died, he passed into the care of a series of guardians who cheated him of most of his inheritance. His desire to sue one of his guardians inspired Demosthenes to take his first steps toward becoming a public speaker.

As a young man, he suffered from a frail physique and a weak, stammering voice. To overcome these problems he supposedly sucked pebbles in his mouth while using his voice to compete with the noise of the sea.

|

Demosthenes was highly renowned for his speechmaking, and his services were in great demand. He struggled to build his reputation and achieved it in part as a speechwriter for those filing lawsuits and spoke in public to plead their case.

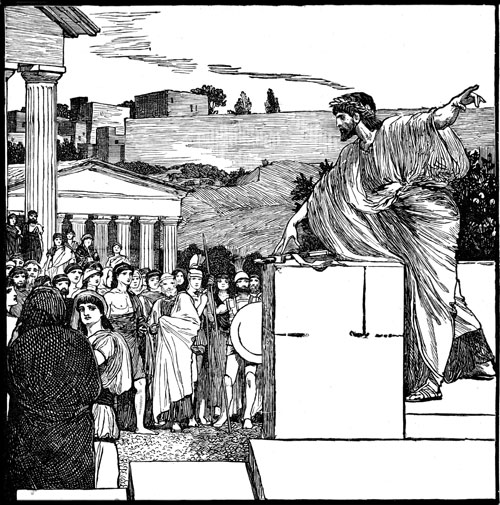

By the age of 30 he had begun to make speeches to the full Athenian assembly (Ekklesia), most notably in connection with the need for Athens to build its naval defenses against a possible resumption of invasion attempts by the Persians. Demosthenes argued the importance of independence and the use of defensive alliances to deter attacks.

Demosthenes made his reputation with speeches that have become known as the Philippics, the orations against Philip of Macedon and the threat the Macedonians represented to Athenian democracy. These were made in the bear-pit atmosphere of the Ekklesia, which was notorious for the rough nature of debate and audience participation. His success led to him becoming one of the most important men in Athens.

His position was consistently in favor of independence, and he was frequently in conflict with interests that would have accepted infringement of civil liberties for the sake of economic development. When Philip’s army started to threaten Athens in earnest, the debate became ever more vociferous. Conflict was avoided primarily because Philip judged the time not yet ripe.

Peaceful relations became increasingly strained as the well-organized and -led Macedonian forces took over ever-greater parts of Greek territory. Ultimately, a pretext arose for Philip to bring the Greeks to battle at Chaeronea, and he delivered a crushing defeat on them. Plutarch claims Demosthenes dropped his arms and ran away from the battle.

Even so, Demosthenes was elected to give the funeral orations and continued to speak in the Ekklesia against Macedonia. When pro-Macedonian support waxed after the accession of Alexander, Aeschines took the opportunity to bring a case that he anticipated would destroy Demosthenes’ reputation.

However, in denying charges of corruption, cowardice, and wrong headedness in a speech known as "On the Crown", Demosthenes routed his opponent, who was subsequently forced to accept exile. This vindication of both his personal integrity and his policies lasted only a few more years.

In 324 b.c.e. Demosthenes was convicted of accepting a bribe and was fined and imprisoned. He subsequently escaped and was even invited back to Athens two years later. However, faced with the opposition of Aeschines, Demosthenes took poison and died. Demosthenes is best remembered for his oratory and some aspects of his political beliefs.