The reputation of Nebuchadnezzar II abounds in the ancient world, as he represents one of the most famous of the Near Eastern monarchs. No fewer than four books of the Jewish scriptures, 10 rabbinic commentaries, six books of the Pseudepigrapha and the apocrypha, several Arabic commentaries, and many classical and medieval Greek and Latin authors mention Nebuchadnezzar, showing his fame and impact on the ancient world.

Many of these sources show him to be godlike and a city builder, while others, especially biblical and early Jewish writers, make him out to be the archetypical villain and city destroyer.

He often appears in the sources as Nebuchadnezzar (mostly in Latin and Greek writings), but more accurately he should be called Nebuchadrezzar (according to the Akkadian and Babylonian version of his name and the Aramaic and Hebrew spellings).

|

His name means "Nabu protects the son (or boundary)". Nabu forms the main root of his father Nabopolassar’s name and is the name of the divine son of the national Mesopotamian god Marduk.

There are at least five other famous Babylonians who take Nabu’s name, including Nebuchadnezzar I, ruler in Second Dynasty of Isin (southern Mesopotamia), 1124–03 b.c.e., from whom his father may have named his son. His life must be reconstructed from disparate and limited materials. Archaeology provides a somewhat sound basis to speak of his tenure as king.

Another somewhat contemporary and cuneiform record is the Babylonian Chronicles, but there is a 30-year gap in its account of Nebuchadnezzar. The gap is filled in by Jewish biblical accounts and by the history of Josephus, writing many centuries later.

The Neo-Babylonian Empire replaced the empire of Assyria in 612 b.c.e. under Nabopolassar. It was built on a hybrid of peoples, one of which was the Chaldeans of southern Mesopotamia. There is some evidence that Nebuchadnezzar’s family descended from the Chaldeans.

One of Nebuchadnezzar’s marriages was to a Median princess, an arrangement meant to keep security among the major powers (like the Medes and Persians) of the eastern Fertile Crescent so that the Babylonians might venture westward.

He accompanied his father on several campaigns and was with him at Carchemish in 608–607 b.c.e., a major frontier city on the Euphrates River, held by the Egyptians. His father had to return to Babylon, but Nebuchadnezzar stayed on and successfully fought the army of the pharaoh Neco.

The Egyptian army was vanquished, and the world of Syria, Phoenicia, and Judaea lay open to him. News of his father’s death, however, interrupted his plan, and he rushed back home to claim the throne. Then he swept to victories across the Levant in 601 b.c.e., and cities throughout the region were forced to pay tribute.

At this point the Jewish Bible is important as a commentary on Nebuchadnezzar, for the Babylonian Chronicles is silent. Judah, the southern counterpart to the now defunct kingdom of Israel, chafed under the burden of Babylon’s domination.

|

The kings of Judah miscalculated the strength and resolve of the Egyptians to help them, and they let domestic hotheads and fanatics lead them into open rebellion against their overlords.

By 587 b.c.e. Nebuchadnezzar surrounded and besieged the city of Jerusalem. On July 30 the Judaean king and his family were humiliated, the city fell, and the Babylonian army deported the citizens. Only poor peasants were left behind in Judaea. All the Temple’s treasures and cultural trappings were exported to Babylon.

For the people of biblical Israel this event became a turning point in their national identity. The central image in the biblical books for this period is Nebuchadnezzar’s destruction of the Temple, his captivity of their leading citizens, and his branding of their status as Diaspora.

In retrospect the Babylonian foreign policy was more merciful than that of the Assyrians, for Nebuchadnezzar did not totally disintegrate the structures that hold a people together (religion, family life, social customs). In fact, Nebuchadnezzar left enough intact that 50 years later the captive people could return and reconstitute themselves as a nation.

Even the famous prophet Jeremiah counseled his fellow religionists to cooperate with Nebuchadnezzar and his ilk. But the enormity of the loss of land and temple forever colored the evaluation that writers of the biblical tradition would have of Nebuchadnezzar. They caricatured him in the darkest hues.

For Nebuchadnezzar’s later years as king inscriptions, archaeology, and later writings must fill the gap. He never was able to invade Egypt successfully or enduringly. Instead he seems to have devoted himself to public works and beautification.

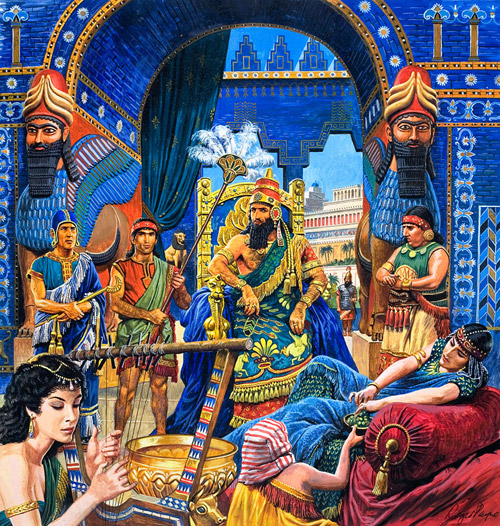

The empire he led reached its pinnacle of power and prosperity under his rule. His construction program involved at least 12 cities in his own land, and he lavished the empire’s resources on his capital city. Excavations suggest that five walls surrounded the city, with towers perched at various strategic places. In addition a moat protected the whole boundary.

He was not satisfied to live in his father’s palace but constructed a dwelling for himself using the most valuable of materials such as gold, silver, lapis lazuli, ivory, and cedar. He restored the city’s temple of Marduk with a tower (ziggurat) perhaps popularly associated with the biblical Tower of Babel (anachronistically placed in the Bible at an earlier Babylonian period).

For all these reasons he wins adulation from later classical historians. For example, the Greeks considered him as the patron of the hanging gardens, one of the Seven Wonders of the World.

Judging by the extant physical evidence he was not so much of a military general as a good administrator and planner. Nebuchadnezzar made his capital one of the splendors of the ancient world. The Neo-Babylonian Empire was not able to maintain Nebuchadnezzar’s splendor in later generations.

Either his descendants did not show the same leadership, or the resources were exhausted, but the empire soon succumbed to the Medes and Persians. In the biblical books of Daniel and Judith, a whole image of the man is projected to the readers.

He comes across as a man of clear intellect and sophistication, though he literally goes mad because of his egomania. The later stories suggest that he became sympathetic to biblical religion later in his life, though his egomania fatally afflicted his descendants’ ability to maintain the Neo-Babylonian Empire.